KLH Model Five loudspeaker By Ken Micallef

KLH Model Five loudspeaker

Stereophile.com

In May of 2019, I heard about a promising jazz vinyl and hi-fi estate sale happening on New York’s Upper East Side. Little did I know then what treasures the dig would yield.

Jazz Record Center’s Fred Cohen had called from the UES apartment, the former residence of late CBS Records and Sony Entertainment mastering engineer Harry N. Fein. Fred said, “The records are kind of beat, but the apartment is jammed with tape decks, turntables, cartridges, tubes, midcentury modern furniture—get up here.”

I called NYC turntable technician Mike Trei, who’s always up for a dig. Upon picking me up from my Greenwich Village pad in his pearl-black 1991 Mercedes, we zoomed uptown on Park Avenue. Well past Grand Central Station, we found the address on a quiet residential block.

At the doorway to the apartment, two muscled Russians were removing a ratty red velvet couch. We squeezed past them into a tiny living room. Books were strewn everywhere. A window sucked in hot, sticky air. A Zenith Seville console stereo, a crusty BSR McDonald turntable, and a ’60s-era Ampex Model AG-350-2 ½” tape machine stood sentry. Where were the records and other audio booty Fred spoke of?

Mike found a side door, jammed shut. We applied two-shoulder pressure and stumbled our way in. The 10′ × 6′ space—Fein’s secret workshop—was a time traveler’s dream of audio exotica.

Dixieland, swing, comedy, and vocal albums lined an in-wall case. Fein’s CBS mastering work was represented: Grachan Moncur III & The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra’s Echoes of Prayer, The Billie Holiday Story Volume II, and Jingle Bell Jazz. A Teac SX-3300 reel-to-reel deck sat on the floor. I pulled open a drawer crammed with Fairchild 225A mono, GE VR-1000, and Shure V15 cartridges. A closet produced a Scott Stereomaster 299-f integrated amp and a slate-gray, Streamline Moderne–looking Fairchild Model 202 tonearm complete with three Fairchild mono carts in turret headshells. Wedged into the back of the closet, their chunky cabinets faded and scratched, grilles seemingly blanched yellow by the sun, was a pair of vintage KLH Model Five loudspeakers.

Produced between 1968 and 1977, the KLH Model Five—like its siblings Models Six and Seventeen—was one of the most popular American loudspeakers ever.

KLH Research and Development Corporation was founded in 1957 by Henry Kloss, Malcolm Low, and Joseph Anton Hofmann. As John Atkinson wrote in 40 years of Stereophile: The Hot 100 Products, “The late Henry Kloss had the Midas touch: whatever his fancy alighted on turned into sonic gold.”

At KLH, Kloss developed the Model Eight FM table-top radio, the Model Nine electrostatic loudspeaker, the Model Eleven record player, and the first reel-to-reel tape recorder to include Dolby noise reduction: the Model Forty. Kloss also founded Advent Corporation (1967), Kloss Video Corporation (1977), Cambridge SoundWorks (1988), and in 2000, Tivoli Audio. And three years before KLH was established, Kloss and inventor/teacher Edgar Villchur launched Acoustic Research, Inc. (“AR”), which mass produced the country’s first sealed-box, acoustic suspension loudspeaker (the AR-1) and first suspended turntable (the AR XA), both affordably priced.

Like Acoustic Research’s popular AR-3a loudspeaker, the original KLH Model Five produced clean, tight bass owing to its acoustic suspension design, a departure from the then- (and now-) ubiquitous bass reflex designs. The Model Five included a 1.75″ pulp-paper tweeter, dual 4″ cone midrange drivers, and a 10″ paper-cone woofer mounted to the front baffle of a sealed plywood cabinet weighing 54lb. Reported impedance was 8 ohms.

KLH went kaput when its Japanese owner, Kyocera Ltd., terminated production of the legacy brand in 1989. Nearly 30 years later, in 2017, former Klipsch global sales president and Voxx Electronics executive David Kelley purchased KLH. Kelley relocated KLH HQ to Noblesville, Indiana, and relaunched the company in late 2018 with no fewer than 30 new loudspeaker models.

The New Model Five

“We started development of the new Model Five two years ago,” KLH chief designer Kerry Geist wrote in an email. “Development was put on hold in early 2020 due to the pandemic, … but the desire was always there to bring back some of the better-known KLH models.”

The revived Model Five shares the original’s cabinet dimensions; three-way, acoustic suspension design (but with just one midrange driver, not two); and vintage-looking grille (a Stonewash Linen grille is available at $199/pair) with new drivers and crossover. KLH retained the zinc logo affixed to the speaker’s grille, and the price is still affordable ($1998/pair), but this isn’t Henry Kloss’s Model Five.

“We wanted to pay tribute to the original Model Five,” Geist told me, “but the goal was never to replicate the sound of the original. I looked at it from the standpoint of how the Model Five, with its acoustic suspension design, would be conceived and designed today. However, a 10″ pulp-paper woofer, mounted in the exact same cabinet dimensions and internal volume as the original, will ensure some amount of performance commonality. [But] transducer design (and testing) has come a long way in 50 years, and that translates to much better overall performance.”

Manufactured in China, the Model Five employs a 1″ aluminum-dome high-frequency driver with soft-rubber suspension; a 4″ pulp-paper cone midrange driver, and a 10″ pulp-paper cone woofer driver. The mid- and low-frequency drivers utilize reverse-roll rubber suspensions and nonresonant, die-cast aluminum frames. The 13.75″ wide, 26″ high, 11.5″ deep cabinet is constructed of structurally reinforced ¾” MDF and weighs 44lb. The M5 is rated at 6 ohms nominal impedance with an in-room sensitivity of 90.5dB/2.83V/m. (The free-field sensitivity is 87.5dB/2.83V/m.) Each KLH Five comes with its own powder-coated, 8″ high, 14-gauge steel, 5°-slant riser base for the “proper angle to ensure the best vertical coverage for all listening positions.” Two finishes are available: English Walnut and West African Mahogany.

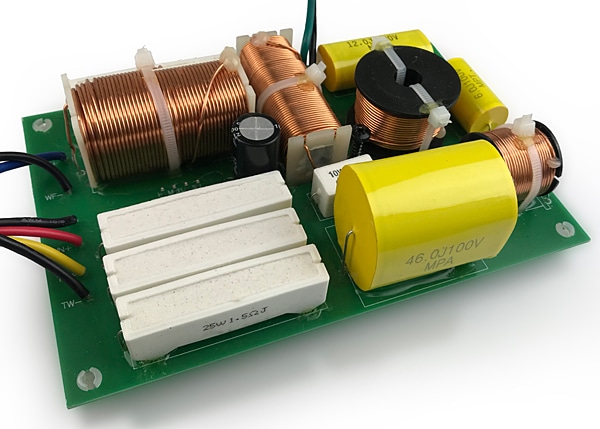

In addition to upgrading its drivers, Geist overhauled the M5’s crossover, a 13-component network that uses iron-core inductors and Mylar capacitors. “The crossover is all 2nd order, 12dB/octave,” Geist explained. “The low-pass woofer and high-pass midrange cross over at about 380Hz, low-pass midrange and high-pass tweeter at 2850Hz. The crossover is comprised of four inductors, four capacitors, [and] five resistors. Three of the resistors are used in the attenuation circuit for the switch located on the back panel.”

Taking different-sized rooms and varying acoustics into consideration, Geist incorporated a three-position attenuator switch (marked “LO, MID, HI”) on the M5’s backside (above a pair of gold-plated binding posts), a holdover from the original M5—sort of.

“The switch attenuates/decreases output above 400Hz,” Geist explained. “I’m not a huge fan of attenuators on loudspeakers because of the affect they have on voicing of the loudspeaker. So, I repurposed the attenuator switch to deal with difficult room acoustics. The amount of attenuation is relatively small (0, –1.5dB, –3dB), over a broad frequency range. The idea is to pull some excess energy out of an overly bright listening room.”

Geist believes that today’s often bass-dense music formats are better reproduced with acoustic suspension speakers. “Today, recordings are … not restricted below 50Hz,” he proffered. “Bass-reflex designs really struggle with anything below the tuning frequency of the port. Their output falls off a cliff, and the system becomes unstable. The acoustic suspension design … [relies] on the air spring the sealed enclosure provides. This air spring is never compromised, so the system output is more stable throughout the low-frequency spectrum.”

Listening

In my system, an 8′ pair of AudioQuest Robin Hood speaker cables linked the Model Fives to, variously, an LKV Research Veros PWR+ power amplifier (200Wpc into 8 ohms, 400Wpc into 4 ohms), Parasound Hint 6 Halo integrated (160Wpc at 8 ohms, 240Wpc at 4 ohms), and Schiit Ragnarok 2 integrated amplifier (60Wpc at 8 ohms, 100Wpc at 4 ohms). I burned in and evaluated the M5s using Roon/Tidal streaming via laptop to the preamp/DAC section of an Ayre EX-8 2.0 integrated amplifier, connected via a 2m run of AudioQuest Forest digital USB cable. A 2m pair of Triode Wire Labs Spirit II interconnects joined the Ayre EX-8 (employed as a preamp) to the LKV Research power amp. Vinyl LPs saw action vis-à-vis my Kuzma Stabi R/4Point tonearm/Denon DL-103 cartridge/Tavish Audio Design Adagio phono stage into either the Ayre, Parasound, or Schiit amps, via a 1m pair of Shindo unbalanced (RCA) interconnects

I secured the Model Fives to their boxy metal stands (included) and toed in the speakers to fire directly at my ears. With attenuation set to “HI”—no attenuation—it took me no time to find a spot in which the M5s could sing. 33″ away from the front wall, 59″ apart, and 59” from my listening seat, they cast a wide, high, immersive soundspace with well-defined 3D images. Central image focus was very good on instruments and vocals. As its calling card, the KLH provided some of the tightest, most sharply defined, streamlined bass—acoustic, electric, synth, organ, didn’t matter—ever heard chez Ken. The Model Fives didn’t produce the absolute depth, tone, or sheer low-end mass of my reference DeVore Fidelity Orangutan O/96s, but bass notes have never sounded tighter or more carved in black space here than they did through the Model Five—which inspired me to unearth my drum and bass, EDM, funk, and Wagner records in succession.

The M5’s midrange was consistently meaty and lucid, but some recordings could excite a thin, slightly papery quality from the tweeters; it was recording dependent. Mostly, the speaker played with a detailed, sparkling upper/mid/treble chutzpah that favored and seemed to amplify texture and viscosity. Notes had realistic weight and body. These Model Fives are attention-getters of the first order, delivering a big soundstage and big, juicy dynamics.

Powered by the Ayre integrated used as a preamp and the LKV Research Veros PWR+ amplifier, the M5s parlayed the moody strings of Brahms’s Symphony No.2, performed by the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra conducted by Antal Dorati (LP, Mercury SR90171), into a thrilling swirl of near-psychedelic tones and textures. They played orchestral music with vigor, never breaking up in musical climaxes but, rather, seeming to relish them, nearly zealous in their sense of power and drive. They repeated these feats on Elgar’s Enigma Variations with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Georg Solti (1976 LP, London CS 6984). The M5s played the hard-charging sections of this piece with muscle and power, absorbing me with physical textures and occasional treble glare heard. Spinning tenor saxophonist Michael Brecker’s 1987 debut (LP, MCA Impulse! MCAD-5980), the M5s’ exacting treble highlighted surface noise, but also every jot and tittle of drummer Jack DeJohnette’s Paiste cymbal array, with good tone and body. The M5s recreated all the sustain and decay of the albums’ recording venue, NYC’s Power Station live room, a ’70s-era, all-wood recording space that resembled a cathedral.

The M5 performed similarly meticulous maneuvers on Steely Dan’s final album, Everything Must Go (LP, Reprise Records 603497849109). Through the M5s, drummer Keith Carlock’s Gretsch snare had lightning-bolt snap, good tone and weight, as did the late Walter Becker’s deep, heavily plucked Sadowsky electric bass. The M5s delivered high-resolution fastidiousness and clarity, as far from my vintage, laidback, “pipe and slippers” Spendor BC1s as possible. With almost every style of music and recording, the M5s engaged me and demanded my attention, framing music in bold shapes and tones.

Since the original M5s were popular in the ’70s, I wondered how their descendants would sound with ’70s music. I chose the second album from New York–cum-Massachusetts rock band Thirty Days Out. 1972’s Miracle Lick (Reprise MS 2085) included performances by future Ramones’ manager and TDO bassist Monte Melnick and celebrated vocalists Madeline Bell and Doris Troy. The album’s production epitomized the dry, flat rock sound of an era when drummers taped their heads and studio experimentation was the norm. “The Sun Keeps Right on Shining” includes guitars run through chorus effects, vocals through Leslie cabinets, and thumping, warlike drumming combined with eerie Mellotron. Vocalist Jon McAuliffe sings about future dread and prescient environmental concerns (“The rivers run much slower than they did when we first saw them”). Driven by the Ayre and LKV Research tag team, the M5s framed this power rock in rich vocal tones, detailed guitar and drums, and nimble bass, all within a wide soundstage. My mind drifted back to that foggy era of orange shag carpet, Cheech & Chong records, and bubbling bong water.

Replacing the Ayre/LKV Research combo with the Parasound Hint 6 Halo integrated amp, the M5s grew more precise as if they were gaining confidence and determination. The Parasound is consistently neutral, powerful, and clean. With the Hint 6 behind them, the M5s presented Miracle Lick with focused vocal elocution, nearly etched-in-space bass and drums, and taut dynamics, giving the music a clean-scrubbed bedrock on which to parade TDO lead guitarist, engineer, and producer Jack Malken’s ’70s studio wizardry.

I played another ’70s record, tenor saxophonist Mark Colby’s One Good Turn (LP, Tappan Zee JC 35725), a funky workout with Bob James, Steve Gadd, Gary King, and Mike Manieri. “Skat Talk,” the opening track, is a slick slab of New York City funk driven hard by King’s electric bass and Steve Jordan’s drums—Jordan plays drums on this track only. A walloping, whipsaw groove supports wailing sax and guttural vocal mumbles inside a tricky arrangement. Through the Parasound, the M5s played Colby’s funk with a crispy, airy top end like a cool outer layer surrounding a warm center. The music was ultraclear through the Parasound/M5 duo, from chunky left-channel rhythm guitar to chatty right-channel agogô bells.

On Sonny Rollins’s Tenor Madness (LP, Prestige PRLP 7047), a mono LP, I could hear John Coltrane’s and Sonny Rollins’s tenors reflecting off the wood cathedral ceiling of Englewood Cliffs’ studio, Trane’s horn chewy and urgent, Rollins’s fuller and more romantic-sounding through the river-clear Parasound/M5 duo. The Parasound’s clarity sometimes pushed the M5’s tweeter into slightly unnatural territory, but again, it was recording specific.

I hadn’t forgotten that the M5 had an attenuator on its tweeter. I used it wide open throughout most of this review. Now I dropped the switch a click, which, according to specifications, should result in a mere 1.5dB diminution in tweeter output. But it was too much: The result was a blunting of the treble that I couldn’t live with. I far preferred the wide-open, unattenuated tweeter plus the occasional high-frequency imperfection. Overall, I liked the M5’s highs.

Amplifiers mattered, too, and one combination struck gold. Playing the Colby and Rollins records with the M5s driven by the Schiit Ragnarok 2 integrated, everything became grittier and funkier—in a good way—as if a layer of sonic polish had been removed, instruments becoming more visceral, punchy, and real. Though the Schiit seemed to lessen contrasts between Trane’s and Rollins’s tenor sounds, those sounds grew more tactile, weighty, and meaningful. The Colby record became more direct and potent, with raspier textures, more upfront images, and more impact.

Conclusion

The M5s let me hear all the differences between amplifiers and recordings via its clean treble, open midrange, and controlled, authoritative bass. The M5 was a forensic instrument when needed and an audiophile speaker capable of reproducing rich, true-to-the-source sounds when desired. For not a lot of money. The KLH M5s are intoxication kings, urging me to hear my most beloved vinyl via its big personality and well-scaled dimensionality.

I thought, “If only I’d kept that pair of original M5s I found uptown!” But the revived KLH Model Five turned any regrets into a hearty smile of satisfaction.